It is made from untanned animal skin, usually calf, sheep, or goat. It’s a durable writing support that has been used for centuries. It is also very reactive to microenvironmental changes – it can shrink, bend, and deform. Returning them to their original form can be challenging. Even with extensive research, parchment is an unpredictable “living material” and each project requires bespoke solutions and careful handling.

Coat of Arms

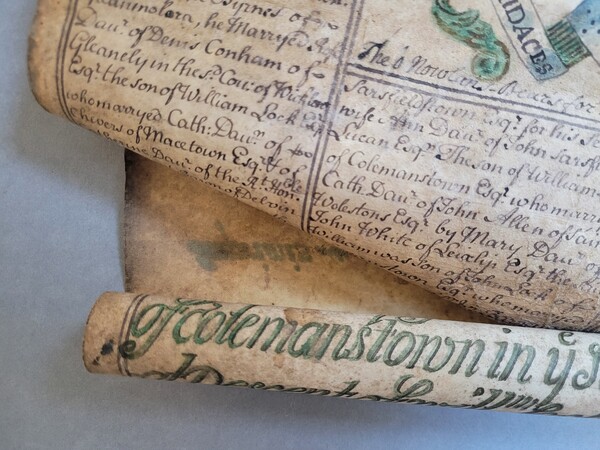

A painted 18th-century parchment manuscript featuring the coat of arms of John Lock of Agoe in the County of Dublin arrived in the Conservation Department curled upon itself, as a result of exposure to climate fluctuations [Fig.1]. Parts of the text were illegible [Figs. 2–3], so my goal was to carefully unroll the document to allow it to be read and stored safely.

[Fig.1] The main fold of the parchment, which limits access to the text.

[Fig. 2] The media on the visible areas is damaged and slightly faded, and the title is not legible.

[Fig. 3] The media on the visible areas is damaged and slightly faded, and the title is not legible.

Conservation Treatment

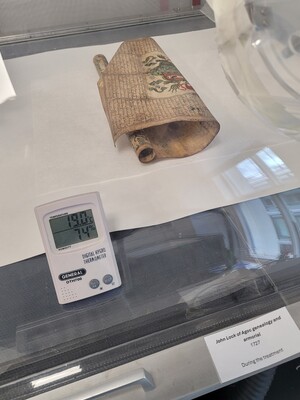

Parchment can be quite rigid after deformation. To relax the collagen fibres, humidity must be gradually introduced into the system. In this case I used a humidification chamber - a transparent dome connected to an ultrasonic humidifier that allows for constant monitoring of the parchment’s reaction to humidity [Fig. 4].

[Fig. 4] The humidification chamber with controlled humidity and temperature.

After the parchment has relaxed in the humidity, it needs to be restrained as it dries to avoid the skin returning to its deformed shape. In this case, I used the clip-and-pin method: I first lined a plywood board with absorbent 100% cotton paper and a layer of non-woven polyester tissue. I distributed bulldog clips evenly along the edges of the parchment, taking into account the irregular shape and the location of any weak points. Pins were used to secure everything to the plywood board through the holes in the bulldog clips [Figs. 5–7].

[Fig. 5] The flattening station

[Fig. 6] The parchment under tension

[Fig. 7] The parchment under tension and a detail of the clips and pins.

Mounting

An important aspect of mounting parchment is the use of materials that allow the parchment to move slightly, considering its tendency to expand and contract with changes in climate. Some modern mounting techniques were ruled out due to them being too time-consuming and because access to the blank verso was unnecessary. A common technique is the use of Japanese paper hinges, but that wasn’t appropriate in this case due to the thickness of the parchment and its severe deformation. The more ingrained the deformation is, the more likely it is that the parchment will return to that shape.

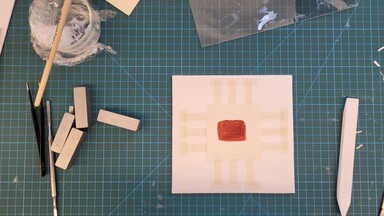

[Fig. 8] One of many tests made to practice with different mounting styles.

I tested different techniques using models to select the most appropriate method [Fig. 8]. In the end, I went with thin self-adhesive polyester hinges applied to the edges and corners of the mount: their flexibility prevents damage to the material, their transparency allows full visual access to all its parts, and their strength will prevent the parchment from rolling back up [Fig. 9-10].

[Fig. 9] A detail of the polyester strips used to mount the parchment on the board.

[Fig. 10] Once flattened and mounted, the parchment is accessible again.

Each parchment object presents distinct challenges, and every project must be assessed in relation to multiple factors, including available space, time and material requirements, environmental stability, accessibility, and storage conditions. Effective conservation of parchment demands a level of preventive analysis and informed prediction of its behaviour in order to determine the most appropriate strategy for long-term preservation. As conservators, we must carefully balance these practical considerations with a fundamental respect for the material integrity of the object.

The manuscript is accessible for consultation in the Reading Room.