This blog examines their relationships and the ways in which these friendships shaped one another’s artistic practice. Heaney’s friendships with these visual artists provided him opportunities to explore the visual arts in his poetry, evoking a strong shared sense of heritage, and what it means to be of a place. The aesthetic sympathies that arise through these artists’ works reveal a unifying ancestral source,

“an omphalos… the first place you come from, the place you belong to, the place where the mother link is holding you." [1]

Each artist was deeply connected to their own omphalos, bonding them to a larger human connection.

A Stream through Sand by T. P. Flanagan

T. P. Flanagan (1929 - 2011)

Flanagan, much like Heaney, was awarded a scholarship to study English at Queen’s University Belfast, but after visiting the city’s museums and galleries he realised it was painting he wished to pursue. He met Heaney in 1960, when Seamus was a trainee teacher. Flanagan credits Heaney with motivating him to try landscape painting; suggesting he keep a journal of childhood trips to Lissadell, which led him instead to sketching and painting the landscape as it fell into nature’s caress.[2]

From Heaney’s perspective, their relationship “coincide[d] with a particularly creative moment in the cultural life of Belfast,” and he considered the Flanagans “sponsors of an opener, fuller, freer, richer life.”[3] Flanagan discovered the landscapes of north Donegal during holidays in 1966, in Heaney's company. He found an invigorating alternative in Donegal’s bogs, mountains and coastline. Using low tonal values and a restricted palette, he captured the harsh forces of the landscape in abstracted forms.[4]

Heaney remembered the Donegal trip vividly:

“On the shore, on the roadside… his sketch-pad would be out… He taught me to see blackness in brightness… every time I look at the sinuous dark line he made of that stream through sand, the excitement of his insight returns.”[5]

Anvil Rock III by Colin Middleton

Colin Middleton (1910 – 1983)

Michael Longley wrote that Middleton’s “abilities and endless inventiveness have taken his work through a number of very distinct phases.”[6] Middleton drew inspiration from myriad artistic movements including Impressionism, Surrealism and Abstractionism. He saw his range as an intimate response to the subject matter and felt that to limit himself to a single style would diminish his powers to express the intricacies and symbolism that he intended his work to exude.[7]

Colin and his wife were often invited to the Heaney’s home for late nights of music, singing and drinking.[8] Seamus frequently spoke at art exhibition openings nationwide, and was invited to open a 1985 retrospective of Middleton’s work just two years after he passed. Speaking of his friend’s artistry, Heaney said “The inspection…took place on the spot…became illumination on the canvas,” remarking that Middleton’s abstracts “often have the look of a vellum perfectly inscribed.”[9] He noted his “pristine responses to the natural world,” linking him to “the world of craft guilds,” the “Celtic penman,” and the “hermetic schoolman.”[10] Heaney felt,

“if Yeats could see paradise through the collar bone of a hare, Colin Middleton could see his way to heaven through the eye of a nib.”[11]

Megaceros Hibernicus by Barrie Cooke

Barrie Cooke (1931 – 2014)

Barrie Cooke’s closest friends were poets: Seamus Heaney, Ted Hughes and John Montague in particular. Heaney was one of the few people with whom Cooke was prepared to discuss his work; he in turn sent Cooke draft verses for appraisal. Cooke inspired Heaney to write, including the unpublished poem The Island, and Heaney credited Cooke and Hughes with persuading him in 1972 to quit his lectureship, move to Co. Wicklow and commit himself fully to poetry.

Heaney later wrote:

“Your confidence in us engendered confidence in ourselves… after that morning's walk at Lugalla and… when we ate the pike. The first supper!”[13]

Cooke had begun experimenting with ceramic Bone Boxes, which intersected with Heaney’s work on the Bog Poems. Heaney recalled “Thinking about them brought up memories of bones I used to find in the fields around Mossbawn,”[13] which fed into Bone Dreams (dedicated to Cooke).

In 1975 they collaborated on Bog Poems, a limited edition featuring eight poems by Heaney alongside full-page illustrations by Cooke. Word and image complement each other, creating a dynamic dialect.

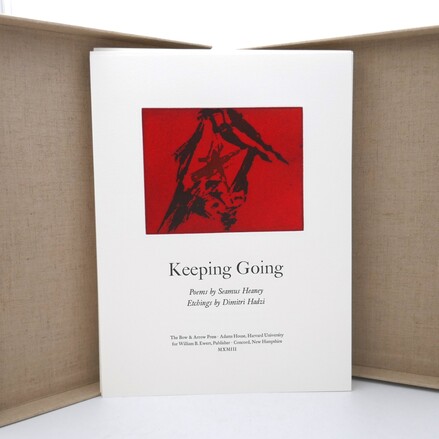

Keeping Going (etching) by Dimitri Hadzi

Dimitri Hadzi (1921 – 2006)

Heaney met Hadzi during his time teaching at Harvard. He described Hadzi’s sculptures as having:

“the deeply satisfactory self-sufficiency of all finished work… a combination of confidence and impersonality, muscle and nimbleness, historical echo and original forthrightness.”[14]

Their friendship was grounded in their shared love of Greek myth. They collaborated on Keeping Going (1993), and Heaney dedicated poems such as Sonnets from Hellas and Mycenae Lookout to the Hadzis. In 1995 they travelled through Greece together—Ancient Corinth, Mycenae, Epidaurus, Arcadia, and Sparta. It was during this trip that Heaney learned of his Nobel Prize. Hadzi recalled Marie receiving the call, “shriek[ing],” and the group celebrating with:

“unremarkable domestic champagne,” “twining caper branches in the absence of laurels, we attempted to crown Seamus with the wreath.”[15]

Heaney’s relationships with Flanagan, Middleton, Cooke and Hadzi show how visual artists influenced not only his poetic output but his understanding of life and human connection. Their dialogue, between word and image, past and present, man and nature, reminds us that creativity is a collaborative act, nourished by people and places where the mother link is holding us.

Explore Seamus Heaney’s friendships and his ties to the art world in our free exhibition Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again.

Sources:

[1] Heaney, Seamus, Afternoon Plus, Interview with John Edwards, Thames TV, 1980 - YouTube

[2] White, Lawrence William, Flanagan, Terence Philip ('T. P.'; 'Terry'), Dictionary of Irish Biography

[3] Foreword by Seamus Heaney taken from Kennedy, S.B., T. P. Flanagan, Four Courts Press, Ulster Museum, 1995

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] TRACE OF A THORN – Colin Middleton, narrated by Michael Longley. BBCNI Documentary filmed c. late 1970’s, YouTube

[7] Ibid.

[8] O’Driscoll, Dennis, Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney, Faber & Faber, 2008

[9] Incomplete manuscript draft of an address on the work of Belfast artist Colin Middleton, 1985 - vtls000362839 | Record | NLI-Hydra

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Reid, Christopher, The Letters of Seamus Heaney, Faber & Faber, 2023, pg. 79/80

[13] O’Driscoll, Dennis, Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney, Faber & Faber, 2008

[14] Heaney, Seamus, Dimitri Hadzi, Hudson Hill Press, NY, 1996

[15] Hadzi, Dimitri, Where in Hellas Was Seamus Heaney, Harvard Review, no. 10, 1996, pp. 27–29. JSTOR